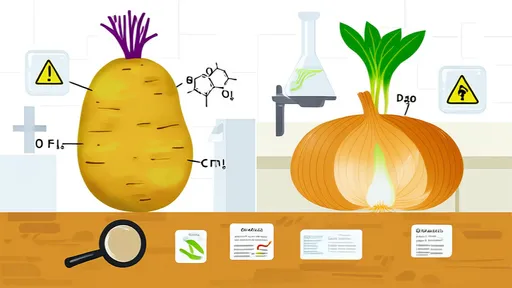

In the world of root vegetables, few debates spark as much confusion as the safety of sprouted potatoes versus sprouted onions. While both are pantry staples, their chemical transformations during sprouting lead to dramatically different outcomes—one potentially toxic, the other benign. Understanding the science behind these changes could prevent food waste and, more importantly, protect your health.

When potatoes begin to sprout, they undergo a fascinating yet dangerous metamorphosis. The greenish tint that often accompanies sprouts signals the production of solanine and chaconine—two glycoalkaloids that serve as the plant’s natural defense against pests. These compounds are no joke: consuming them in high concentrations can cause nausea, neurological disturbances, and even organ failure. The sprouts themselves concentrate these toxins, but the danger extends to the potato’s flesh, especially near green patches. Peeling deeper or discarding the vegetable altogether becomes the only safe option.

Contrast this with onions, whose sprouting process tells an entirely different story. Those green shoots emerging from the bulb might look unappetizing, but they’re essentially just immature onions. Unlike potatoes, sprouting doesn’t trigger toxic compound production in onions. The texture might turn woody, and the flavor could intensify, but you’re more likely to encounter culinary disappointment than actual harm. In fact, many cultures intentionally grow onion sprouts as garnishes or salad ingredients.

The divergence stems from these vegetables’ evolutionary strategies. Potatoes, being tubers that grow underground, developed chemical warfare to deter predators. Onions, however, evolved above-ground bulbs that rely on pungent sulfur compounds (harmless to humans in normal quantities) for protection. When an onion sprouts, it’s simply attempting to grow into a new plant—a process that doesn’t involve toxin synthesis.

Storage conditions dramatically influence sprouting behavior. Potatoes kept in bright light ramp up solanine production at alarming rates, while onions stored alongside potatoes actually sprout faster due to ethylene gas exposure. This explains why grandmothers always insisted on keeping them in separate, dark, well-ventilated spaces—a practice now validated by food science.

Modern agriculture has compounded the potato issue. Commercial varieties bred for high yields often have thinner skins and lower natural toxin levels, making them more susceptible to dangerous sprout-related chemical spikes. Heirloom potatoes, with their thicker skins and robust defenses, might show visible sprouting before reaching hazardous toxin levels—a nuance lost in industrial food systems.

The culinary implications are equally intriguing. While sprouted onions can be used creatively (the greens make excellent chive substitutes), attempting to salvage sprouted potatoes by cutting away affected areas requires precision. The knife must excise not just the sprout but a generous portion of surrounding flesh, as toxins migrate outward. When in doubt, composting becomes the safest recipe.

Food safety organizations have struggled to communicate these nuances. Blanket "discard sprouted vegetables" advisories fail to distinguish between species, leading to unnecessary food waste. Meanwhile, social media myths about "potato sprout tea" detox remedies persist despite medical evidence showing the opposite effect—these brews concentrate glycoalkaloids to dangerous levels.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity. Warmer global temperatures accelerate sprouting in both vegetables, but potatoes become hazardous faster in heat. Researchers are now developing sprout-inhibiting technologies, from natural essential oil coatings to gene-edited varieties that delay sprouting without increasing toxins.

Historical accounts reveal how civilizations navigated these risks long before modern science. Andean cultures developed elaborate freeze-drying methods for potatoes that prevented sprouting, while ancient Egyptians stored onions in woven baskets that allowed airflow. These traditional practices often aligned perfectly with what we now understand about food chemistry.

For home cooks, the practical takeaways are clear: store potatoes and onions separately in cool darkness, inspect potatoes rigorously before use, and embrace sprouted onion greens while composting questionable potatoes. Food scientists emphasize that when it comes to sprouted tubers, "better safe than sorry" isn’t just a cliché—it’s a matter of physiological consequence.

As research continues, we may see smarter storage solutions or even bioengineered potatoes that sprout without becoming toxic. Until then, respecting the fundamental differences between these common vegetables ensures both safety and sustainability in our kitchens. The humble potato and onion, it turns out, embody one of nature’s most striking examples of how similar processes can yield opposite outcomes.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025