In kitchens across the world, the practice of saving leftovers is as common as cooking itself. While reheating yesterday’s dinner might seem harmless, emerging research reveals a startling truth about leafy greens—their nitrate content can double within just 24 hours of storage. This silent transformation poses underrated health risks that many home cooks overlook.

Leafy vegetables like spinach, lettuce, and bok choy naturally contain nitrates, compounds that are benign in fresh produce but become problematic as they break down. When these greens are chopped, cooked, and left at room temperature or even refrigerated, bacterial activity converts nitrates into nitrites and eventually into nitrosamines—a known carcinogen linked to digestive cancers. The speed of this chemical metamorphosis is far quicker than most consumers realize.

Laboratory studies tracking nitrate levels in stored cooked spinach show concentrations spiking by 110-130% after one day. What makes this particularly alarming is how these vegetables are frequently portrayed as health foods. Parents might feel virtuous serving reheated greens to children, unaware they could be introducing harmful compounds. The irony is palpable—the very foods promoted for preventing disease might contribute to it when improperly stored.

Temperature plays a crucial role in this dangerous alchemy. While refrigeration slows the process, it doesn’t stop it entirely. Cooked greens left at room temperature for just two hours before refrigeration undergo even faster nitrate conversion. Restaurant takeout boxes and meal-prep containers often sit in this danger zone longer than people realize, especially during summer months or in warm climates.

The body’s reaction to these transformed compounds creates another layer of risk. Nitrites bind to hemoglobin, reducing the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity—a particular concern for infants (leading to blue baby syndrome) and individuals with respiratory conditions. While adults have more robust detoxification systems, chronic exposure through daily consumption of high-nitrite leftovers may overwhelm these defenses.

Not all vegetables undergo this risky transformation equally. Root vegetables like carrots and potatoes show minimal nitrate increases during storage. The cellular structure of leafy greens—with their large surface area and delicate cell walls—makes them uniquely susceptible to rapid nitrate conversion. This explains why food safety agencies specifically warn against reheating spinach multiple times while allowing more flexibility with other veggies.

Modern food preservation methods offer partial solutions. Vacuum-sealing cooked greens can slow bacterial growth, while quick-freezing creates ice crystals that disrupt nitrate-converting enzymes. However, these approaches require equipment beyond standard kitchen tools. For most households, the practical solution lies in portion control—cooking only what will be eaten immediately—and rethinking our cultural acceptance of next-day greens.

Food safety guidelines haven’t adequately communicated this specific risk. General warnings about bacterial growth in leftovers overshadow the quieter, chemical-level changes occurring in plant matter. Nutrition labels don’t account for post-purchase nitrate spikes, leaving consumers without crucial information. This knowledge gap becomes dangerous when health-conscious individuals unknowingly consume greens at their most chemically volatile stage.

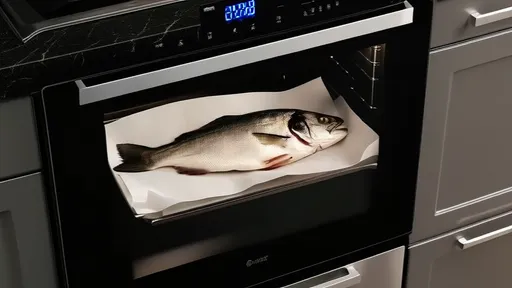

The culinary world isn’t helping either. Popular meal-prep culture glorifies cooking large batches of greens for the week, while restaurant portion sizes encourage taking home half uneaten meals. These practices collide with scientific reality—that the healthiest way to eat leafy greens might be the most immediate way. Perhaps it’s time to reconsider our relationship with these vegetables, treating them more like fresh seafood than shelf-stable grains.

As research continues to uncover the hidden biochemistry of stored foods, consumers face difficult choices between convenience and safety. The nitrate dilemma in leafy greens represents just one example of how our modern eating habits outpace evolutionary adaptation. While our ancestors rarely faced this issue—eating greens immediately after harvest—we’ve created storage conditions that transform healthy foods into questionable ones, all while believing we’re making nutritious choices.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025